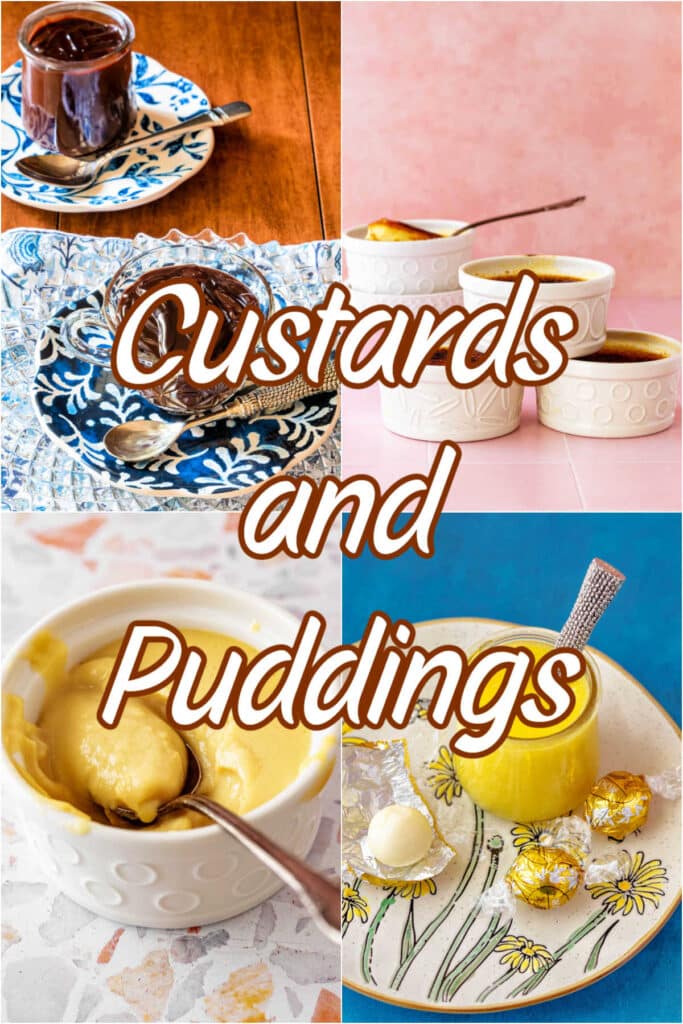

In this post, I want to get deeper into the similarities and differences between custards and puddings–egg thickened, usually sweet desserts, made with or without starch.

Custards can be baked or stirred, and the resulting properties will be different.

This post is part of my Pastry Techniques series and is also an answer to a question a reader asked. Let’s dive in.

Pastry Chef Online Participates in Affiliate Programs. If you make a purchase through one of my links, I may earn a small commission. For more information click to read my disclosure policy

What’s Covered In This Post, At a Glance

✅Main characteristic of a custard (thickener)

✅Stirred versus Still Custard

✅Starch versus No Starch

✅Use of a Double Boiler

✅Putting What You’ve Learned to Use

Related Reading:

Tempering Eggs

I Really Am Here to Help

A reader, Pam, “delurked” yesterday to ask for clarification about putting together a custard. When to use butter; when not to use butter.

She also said (tongue in cheek, I hope) that she was afraid that I would tap my foot disapprovingly and ask her why she hadn’t been paying attention all along. Well, fear not, Pam. I have decided that I am just not that person.

A few months ago, before I started this wee blog and before I started truly understanding the level of hesitancy out there when it comes to cooking, I made the conscious decision not to be the food snob who rolls their eyes at folks who think foie gras sounds “icky,” or to smugly smirk when someone tells me that their favorite restaurant is Chili’s.

I have given myself the job of demystifying recipes, not denigrating those who try to follow them.

In my current kitchen view, a recipe is a list of ingredients that has been stapled to a description of the technique/techniques for combining said ingredients. So, to avoid confusion, I thought I’d give you a bit of a technique primer.

Puddings and Custards

Custards are thickened with the power of eggs.

Some use yolks, some use whole eggs, some use a mixture of yolks and eggs. Regardless, unless it contains eggs, it’s not technically a custard.

Since eggs are so versatile, there are lots of ways to cook them.

On their own, scrambled, poached, coddled, fried, baked, hard cooked all come to mind.

But when used as one ingredient in a custard, the way the eggs set up determines the style of the custard.

- If you stir and cook a custard to its maximum thickness on the stove top, it’s called a stirred custard.

- If you pour the custard into a mold of some sort and then bake it, it’s called a baked or “still” custard.

- And, in the US, if the custard contains starch, we call it pudding.

- In France, a starch based custard is pastry cream or crème pâtissière.

Still custards are generally the most firm, followed by starch-thickened custards and stirred custards.

The first thing you need to figure out is if the custard has starch in it. Any ingredients like flour, corn starch, arrowroot, etc are starches and lend their thickening power to the custard.

If the ingredient list does contain starch, understand that you will have to fully cook the custard on the stove. This means that you must bring it to a boil and stir it like a crazy person for about 30 seconds (up to 2 minutes if the starch is cornstarch).

This is because most starches aren’t completely activated–swollen up and gelatinized–until they reach boiling temperature. If your recipe calls for starch, make sure you bring it to a boil. If you’ve ever made pudding that tastes kind of chalky, it’s because you didn’t get it hot enough and didn’t let it cook long enough to fully gelatinize.

If the ingredient list doesn’t contain starch, the next step is to see decide if the custard is a stirred custard or a baked/still custard.

If you’re making crème brûlée, you’ll be baking the custard in the oven, so it’s a still custard.

If you’re making eggnog or Creme Anglaise or ice cream base, the custard will be fully cooked on the stove top, so it’s a stirred custard.

The procedure for each will be almost identical, but you won’t continue to cook a base for a still custard after you temper in the eggs.

Custards with starch (American-style pudding)

- Whisk together dairy and half the sugar in a sauce pan.

- Whisk together the eggs/yolks with the rest of the sugar, salt and dry ingredients, including the starch. If the ingredient list doesn’t contain salt, ignore it and add some anyway. Some recipes won’t contain eggs. That’s fine, but you can always add in a yolk or two for richness.

- Bring dairy mixture up to just below a boil.

- Add hot dairy, a bit at a time, to the egg mixture, whisking madly. This brings the temperature of the eggs up gradually and prevents you from scrambling your eggs.

- Pour everything back into the pot. Over medium heat, whisk madly until the mixture comes to a boil. Boil for about 30 seconds.

- Strain mixture through a fine mesh strainer. If the recipe calls for butter, chopped chocolate and/or an extract or liqueur, add it/them now and whisk in until smooth.

Example: My silky vanilla pudding recipe.

Custards (and Curds) without starch

- Whisk together dairy and half the sugar in a sauce pan.

- Whisk together eggs/yolks with the rest of the sugar and the salt. If your ingredient list doesn’t contain salt, add it anyway.

- Bring dairy (or citrus) mixture up to just below a boil.

- Add hot dairy/citrus, a bit at a time, to the egg mixture. Gee, doesn’t all of this sound oddly familiar?

- At this point, if you’re making a still custard, as for crème brûlée or flan, just strain the mixture, pan it up and bake in a water bath at about 275F. If you’re making a stirred custard, keep going:

- Pour the egg mixture back into the pot. Over medium-lowish heat, stir the custard/curd until the mixture thickens and coats the back of a spoon. This happens at around 160F. At this point, you’ll want to cool the custard quickly so it won’t curdle. You can strain it into a metal bowl set in an ice bath and whisk, or you can hold out a portion of the dairy to add back in at the end of cooking. Your choice, but strain the mixture either way.

- If you’re making curd, whisk in the butter after straining.

Examples: Creme Anglaise and Lemon Curd

Double Boiler method

You can make a custard or curd in a double boiler.

If you want to use the double boiler method, add everything except the butter to the top pan/metal bowl. Keep water at a gentle simmer, and whisk constantly until the custard/curd has thickened.

Strain and stir/whisk in butter.

I wouldn’t bother using a double boiler with a starch-thickened custard, though. The starch helps prevent curdling, so you should be fine cooking over direct heat. The double boiler method is good for custards that you want to thicken but not boil.

Use What You’ve Learned

Okay, pop quiz. I give you an ingredient list, you give me the method you’d use to put it together.

Exhibit A (Anglaise)

1 cup heavy cream

2 teaspoons vanilla extract

4 egg yolks

1/3 cup white sugar

pinch of salt

Exhibit B (Chocolate Pudding)

3/4 cup (150 grams) granulated white sugar

3 tablespoons (30 grams) cornstarch

1/3 cup (30 grams) Dutch-processed cocoa powder

1/4 teaspoon salt

2 1/2 cups (600 ml) whole milk

1/2 cup (120 ml) heavy whipping cream

4 large egg yolks

4 ounces (120 grams) semisweet chocolate, finely chopped

1 1/2 teaspoons pure vanilla extract

1 tablespoon (14 grams) unsalted butter, room temperature (cut into small pieces)

Exhibit C (Flan)

2 cups heavy cream

1 cinnamon stick

1 vanilla bean, split and scraped

3 large eggs

2 large egg yolks

Pinch salt

Exhibit D

Okay, this one isn’t an exhibit, really, It’s a question: Which of the three recipes might you want to use a double boiler for? Why?

Questions?

If you have any questions about this post or recipe, I am happy to help.

Simply leave a comment here and I will get back to you soon. I also invite you to ask question in my Facebook group, Fearless Kitchen Fun.

If your question is more pressing, please feel free to email me. I should be back in touch ASAP, as long as I’m not asleep.

Hi, y’all! I hope you’ve enjoyed this post and hopefully also learned a thing or two.

If you like my style, I invite you to sign up for my occasional newsletter, The Inbox Pastry Chef.

Expect updates on new and tasty recipes as well as a bit of behind-the-scenes action. I hope to see you there!

And that’s what I have for you today. I hope this post helps you deepen your understanding of custards and puddings.

Thanks for spending some time with me today. Take care.

Join in Today!

Hi, Jenni, if you’re still “out there.” I have a question for you: I made a stove-top, eggless “custard” recipe from the NYT. I erred by adding lemon juice at the same time I combined the milk and sugar. Am wondering if I totally blew it or if it can be salvaged.

Thanks for your thoughts.

Hey, Christine! I guess this is a lemon pudding? So a starch-thickened, eggless pudding. I would think the starch would mitigate any curdling, but probably after it gelatinizes. My guess is it will be okay, especially if it’s a lemon pudding. If you’re trying to make a plain pudding into a lemon pudding, then maybe not. If it has curdled, you could potentially save it with mad whisking and then straining through a fine mesh strainer. Then check for texture. If it’s “curdy,” you may have to start again, but the pudding won’t be “bad,” per se. Just have an off texture. Hope that helps!

Is there any reason to temper the eggs if making basic custard? I was under the impression tempering was only need when adding eggs to a hot mixture like chicken stock for instance or hot vanilla-infused milk. If you mix the eggs with milk and then heat, you are already heating gradually.

I would say that tempering is kind of a check for people who may not be as diligent as they should be in stirring constantly. But yes, you are correct, that if you add the eggs at the beginning, you’re heating them gradually. And as long as you keep the mixture moving continuously throughout the cooking process, there should be no problem. As a failsafe, I always strain my stirred custards–from Anglaise to plain old pudding–as the last step.

What does the phrase “set up” mean? Especially at the molecular,or chemistry, level

Hey, Mary. When a custard “sets,” it means that the proteins denature and as the custard cools, it firms up. Stirred custards (like puddings) set while being stirred as the temperature goes up, and “still custards,” or ones baked in the oven, set up as the temp increases in the oven. The more slowly you can do this (the lower the temp you cook them at), the creamier your set will be. With stirred custards, which often contain starch as well, can be cooked at higher temperatures and still be creamy since the starch keeps the proteins from denaturing/setting up too firmly so you don’t end up with sweet scrambled eggs. Set is just a visual indicator or verification that the proteins have denatured or unraveled. I hope that helps.

OK, so I’m making what’s probably my millionth pumpkin pie and I forgot to tare the scale when adding the pumpkin. I know, generally, that two eggs will thicken about 4 cups of liquid/other ingredients (for one 9″ pie filling). I now have about 33.5 ounces of filling. Will the two eggs be enough to firm up the filling if I bake it a little longer? Or would it be prudent to add another yolk (which I don’t want to do because I hate “eggy” tasting custards), or a bit of starch?

If you don’t like eggy custards, I think I’d go the starch route for some insurance. Try a tablespoon along with the two eggs and just make sure the I ternal temp reaches 167F to make sure the starch gelatinizes fully.

P.S. the recipe is from American Classics by Cook’s Illustrated, usually a pretty reliable source.

Here is the lemon custard:

6 egg yolks

1c sugar

1/4C cornstarch

1/8t salt

1 1/2C cold water

1T lemon zest

1/2C lemon juice

2T unsalted butter

I think the devil is in the cooking of the custard. Here are the directions:

Mix sugar, cornstarch, salt and water in large, non-reactive saucepan. Bring to simmer over medium heat, whisking occasionally at beginning and more frequently as mixture begins to thicken. When mixture starts to simmer and turn translucent, whisk in egg yolks, two at a time. Whisk in zest, then lemon juice and then butter. Bring mixture to a good simmer, whisking constantly.

Here are my issues:

*How cold is cold water? Why cold?

*Why the yolks straight into the pan and not the reverse or some sort of tempering?

*NOWHERE does the recipe say the consistency expected of the filling, nor does it give a time range for cooking.

Hence, SOUP.

The filling tastes good, but I have never had it come out right, so any suggestions are welcome.

Thank you so much for your help.

You have to cook it until you observe it thickening. Stirring speeds it up, and allows you to use higher heat. Stir quickly once it starts to thicken, moving around the whole bottom of the pot. As for the eggs, they should be added at the beginning before it is hot.

Hey, Chris. Stirring doesn’t necessarily speed things up, but it does help the mixture to thicken more evenly without burning on the bottom. But yes, absolutely you can use a higher heat as long as you are stirring quickly and continuously. I usually add the eggs or yolks in at the beginning with everything, but it is not incorrect to temper them in if you’d rather. It adds an extra step to a stirred custard, but it’s also the old-school way to make pastry cream, whisking eggs with half the sugar and the starch and then tempering before completing the custard.

Dear Jenni,

It worked like a charm!! This is a good thing because my husband said he was going to throw it out. Phooey. Now we are both happy. When I get a minute I will send you the recipe for the custard part of the pie and you can see what’s up.

Thanks a million!

Dear Jennie,